As soon as I got to the track last night, I didn't have any idea what to do with my arms. My walk is bad enough, my arms jerk back and forth in an asymmetrical spasm. But when I'm running I've got a million options: Push my elbows back, or pump my hands down? Loose or controlled? High or low? I'm like the guy on his first acid trip in the Richard Pryor routine: "I don't remember how to breathe! I can't breathe!"

I leaned into the first few warmup sprints, arms noodling to and fro looking for something useful to do. The first sprint I kept them fairly still. The next time I let them pump gently, which felt closer to right, but still awkward.

Arm swing is important. A study released last spring shows that swinging your arms naturally as you run is better than, say, holding your hands behind your head as you run. (As anyone who's had to escape a police car and flee through city streets will understand.) So if you got 'em, swing 'em. But what's the best way to do it?

I mess up the simplest things by reading too much about them. Because there's little science on the subject of arm swing, there's a lot of advice. One book says to pump down with your forearms from the elbows not the shoulders, and imagine you're softly clutching a Dorito in each hand. Another says to swing back from your shoulders, elbows locked at 90 degrees, hands relaxed as if you're holding a butterfly.

I looked around at the other runners on the track. Everyone had their signature stride. One guy's feet darted outward at every paw-back, and another's head pumped like a piston at each footstrike. People's arm swings were just as funky. One woman's elbows rose high and back. A guy running shirtless hardly moved them at all, as if he were cradling a tray (of butterflies or Doritos?) close to his naked chest.

The anthropologist Marcel Mauss, writing in 1934, remarked, "Imagine, my gymnastics teacher, one of the top graduates of Joinville around 1860, taught me to run with my fists close to my chest - a movement completely contradictory to all running movements. I had to see the professional runners of 1890 before I realized the necessity of running in a different fashion."

But Mauss goes on to make the point that there is no one natural way to do anything with your body. All locomotion - walking, resting, swimming, running - is practiced completely differently by different peoples and cultures.

Butterflies and Doritos apart, the best advice came from Coach Tony who told me to make sure the hands are doing the same thing as the feet. It's one of those infinitely interpretable and literally impossible proposals, really wide open, that focuses your attention on the act without telling you what to do at all.

Last night there was a boy of about 8 at the track running in one of the outer lanes with his parents. I was struck by how fast he was. You often hear people say that we should run like children, the natural way. But children, if you take the time to look, have horrible running form. Their legs fly every which way and they can't hold their core still. Don't even get me started on their arm swing.

To run well, you have learn how not to run like a child. I watched the kid at the track try to keep up with my group, and he did very well. He ran with joy and real heart, his elbows out like a grandma at Fairway. But he soon was distracted by something, and his spazzy, happy form had exhausted him after 60 yards.

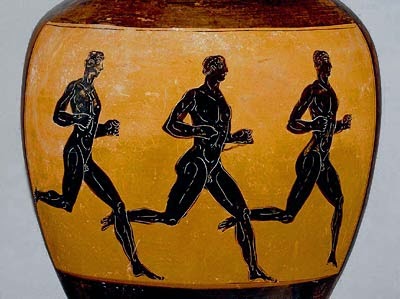

Just as arm swing varies by age, so it will vary by speed. The ancient Greek Olympians on the vase in the image at the top are running a distance event, probably around 2.5 miles. You can tell, in the black-figure pottery of that era, by of the way they hold their arms - out to the front and fairly relaxed. On vases depicting the stadion, or sprint, the runners have high knees and high arms. Very high.

Everyone has a different arm swing, and everyone does it differently at different times. A major conclusion of the study I mentioned above is that runners' different swing styles had no effect on their efficiency - as long as they were swinging them some way or other. As its lead author said, reassuringly, “Most people will settle into the arm swing that is the most efficient for them.”

We were coming around the track for the third time when my arms finally rocked themselves into a rhythm where my trunk felt perfectly balanced and my legs moved easily. I had forgotten to obsess about my arms, and so they figured it out on their own. Which I guess is really the takeaway. The trick of running is not to think too hard about it.

And don't forget to breathe.

July 30, 2014

February 24, 2014

Where was I?

When you're in it, it can be hard to see. Then, mysteriously, it creeps up on you and flattens you. Where does it come from?

Two years ago I was racing every two weeks, and having a great time. I did pretty well. I was in great shape. Why shouldn't I run at 100% effort every 15 days? Ain't I gonna live forever?

Well, it caught up to me, let's just say. I don't regret it. I looked down at my legs the day after my last race, and they looked up at me and rolled their little eyes and said, We're outta here.

My tibialis anterior on both sides were painfully overdeveloped. A rather small flaw in my biomechanics had learned to express itself in a big way, thanks to all the practice it was getting. I ran too hard, too much, and I guess I learned a lot. It seemed surprising at the time, but now of course it's blindingly obvious that injury was the only way that chapter was going to end.

So for two years I didn't race. I scratched Boston (for the second time), changed careers, got periodically busy, and ran only sometimes.

Then this winter, after suffering a cold that lasted six months, I figured it was time to shake things up again. I trained a little, ran a race, and hit the road again.

I'm still overtraining. I haven't learned a thing. Like I said, I don't regret any of it. I got to know myself better. I look forward to interesting injuries, more catastrophic training mistakes, and better failures.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)